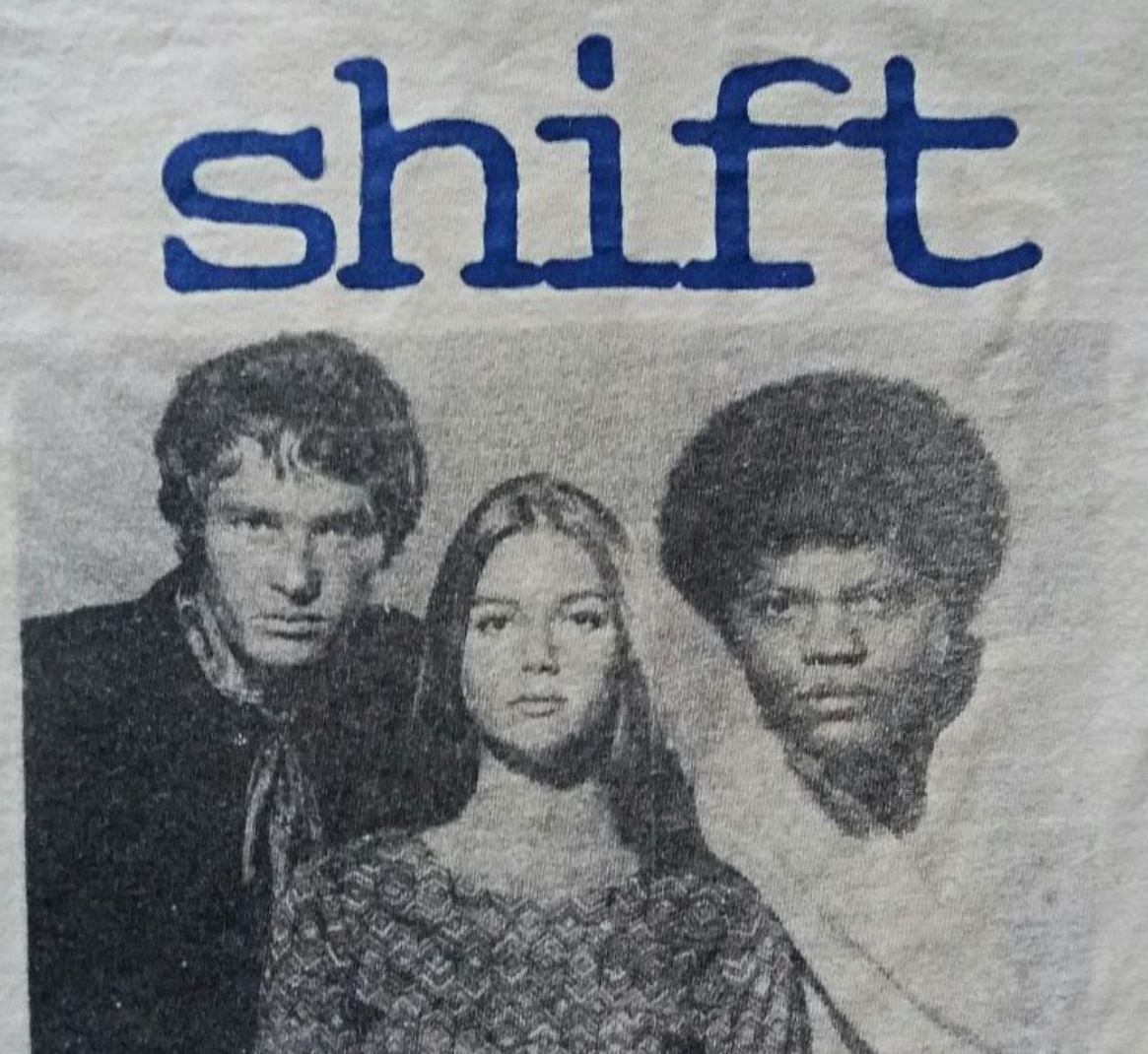

Shift is a band that comes up a lot in my personal life. You see, the NYC band might have broken up in the late '90s, but their drummer, Samantha Maloney, is a close friend from Queens who is not only my son's godmother, but also lives in our neighborhood in Los Angeles. So, it's only natural that I cover Shift on No Echo. But before I go ahead and do a proper interview with Samantha, I wanted to get Josh Loucka, the guitarist/vocalist of the band, on the site since his career has been a bit more behind the scenes since his touring days.

In this new chat, we discuss every facet of Josh's musical life and career to date, including Shift's journey from NYHC's DIY roots to signing with a major label and working with big-name producers. As you'll read, he's transitioned into a successful and interesting career for himself.

It’s funny, but the minute I tell people that I’m originally from New York City, they often assume I mean Manhattan, but I grew up in one of the outer boroughs. But you actually did grow up in the city!

I grew up mainly in the East Village on 10th Street and 3rd ave. My parents divorced when I was 4 and my dad moved down to the corner of Prince and Lafayette — right on the border of Soho and Little Italy — so then I would spend half the week at each apartment. To walk from one to the other, you could walk right past CBGBs — if you wanted to walk down Bowery/3rd Ave — but to be honest, when I was young, Bowery was pretty sketchy, so we would usually walk on Lafayette/4th Ave. This was the early '80s so the whole neighborhood had an intense energy. Lots of punks and weirdos and artists hanging out on St. Marks Place. My corner at 10th and 3rd was apparently a popular hooker spot. I remember any time my mom and I would come home after dark, there would be women in mini-skirts and tube tops hanging out right next to our building and talking to creepy dudes in cars. It’s funny because now that neighborhood is like a squeaky-clean college campus.

My bedroom window actually looked out of the back of the building and faced the corner of 11th st and 3rd ave — which is down the block from where the old Ritz was (which is now Webster Hall). For big shows, the line would wrap around the corner and I remember being a young kid (like 6 or 7) looking out my window wondering what these crazy-looking teenagers were waiting in line for. Apparently Ozzy Osbourne recorded Speak of the Devil there (or at least the parts that they didn’t re-record) in ’82, so I like to think that that was one of the nights I was watching weirdos out my bedroom window, but I can’t be sure.

Are your parents artistic at all, and did they play a lot of music at home when you were growing up?

My parents both played piano and my mom also played Viola. My dad is also a screenwriter, so there was definitely a lot of art going on — but it wasn’t like a full-on hippie commune artsy home either. My parents were really young when I was born (18 and 20 years old) and they both loved listening to music, so I grew up with a lot of great records being played around the house; Stevie Wonder, Sly and the Family Stone, Aretha Franklin, The Stones, Earth, Wind and Fire, the Beatles, etc. The first music I really got into were the newer bands that my dad liked — The Police, Elvis Costello, Talking Heads. Those were the bands that made me realize music was something that was going to be important to me. The Police were my first favorite band, but then when I was 8 (so probably 1983) I discovered heavy metal. We didn’t have cable, but my friends kept talking about this new thing called “MTV.” I couldn’t watch that but then I heard about a show on NBC called Friday Night Videos.

We had just gotten our first VCR, so I asked my mom to program it to tape Friday Night Videos (since it came on well past my bedtime). The following morning, I pressed play on the VHS tape and there was a video “battle” between ZZ Top “Legs” and Def Leppard “Foolin’.” I remember watching the ZZ Top video first and thinking it was kind of cool but then Def Leppard came on and it was like the heavens parted to reveal the coolest thing in the universe. I’m not even exaggerating when I say that I knew at that moment that I would be in a band when I grew up. I was certain my destiny was to actually be Joe Elliot. I taped a magic marker to a broomstick so it looked like a microphone and jumped around on my bed pretending I was him. I asked my mom to buy me a British flag tank top but of course she didn’t know where to find one.

It was Def Leppard first, then Van Halen, Mötley Crüe, Ozzy, Judas Priest. Twisted Sister, Ratt, Maiden, KISS, etc. I went from playing with GI-Joes and He-Man figures to saving up my allowance to buy metal records and t-shirts.

At what age did you discover hardcore and punk music?

Like most young metalheads of the day, when thrash started blowing up around ‘86/’87, I was way into it. Metallica, Slayer, Megadeth, Kreator, Anthrax, Exodus, Nuclear Assault, etc. Then I went over to a friend’s house and he had some of the Earache stuff — Morbid Angel, Carcass, Napalm Death — and that stuff scared the shit out of me but I loved it. I realized there was stuff out there that was more intense than the thrash bands. Also, some of the thrash stuff was kind of goofy and tongue-in-cheek (I’m looking at you Exodus’ “Toxic Waltz”) whereas Napalm Death was definitely not giving off that kind of vibe. I was attracted to the intensity. Meanwhile, I would buy Rip magazine — and I remember they had a short article on this band called Leeway and it said they were from NYC. I thought they looked cool, so I went to Tower Records and bought the Born to Expire cassette and it blew my mind. I thought Metallica was way tougher than the hair metal bands — but then I heard Leeway and I was like, “whoa, this is even rawer and meaner.”

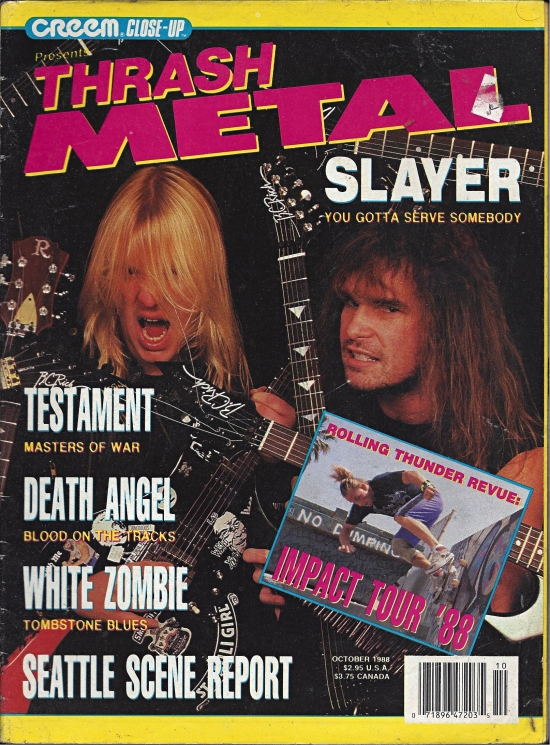

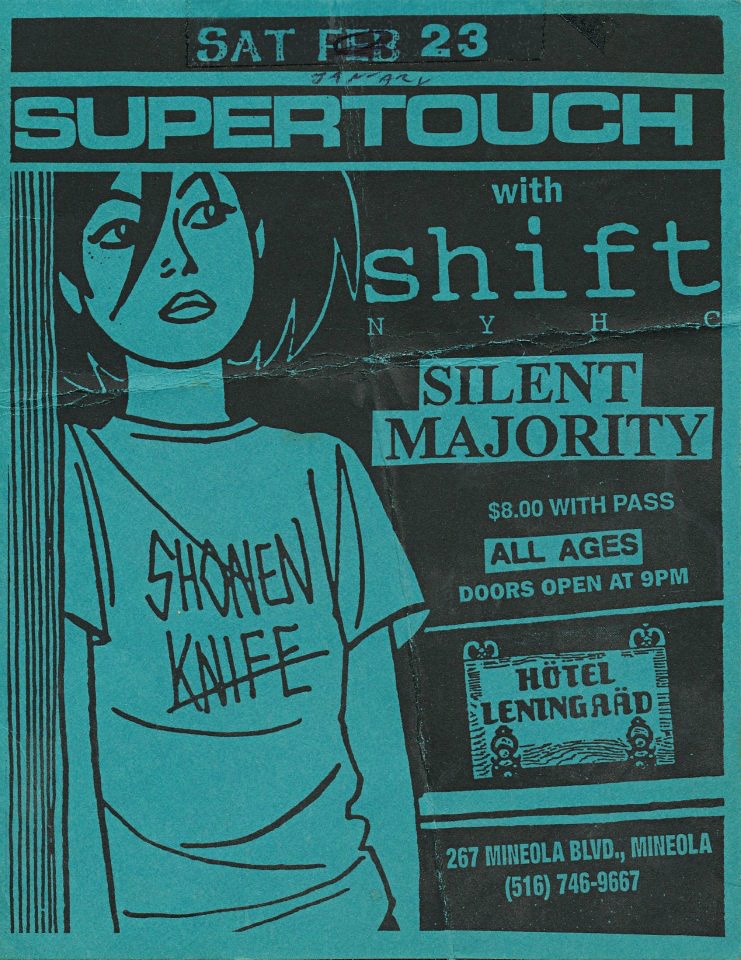

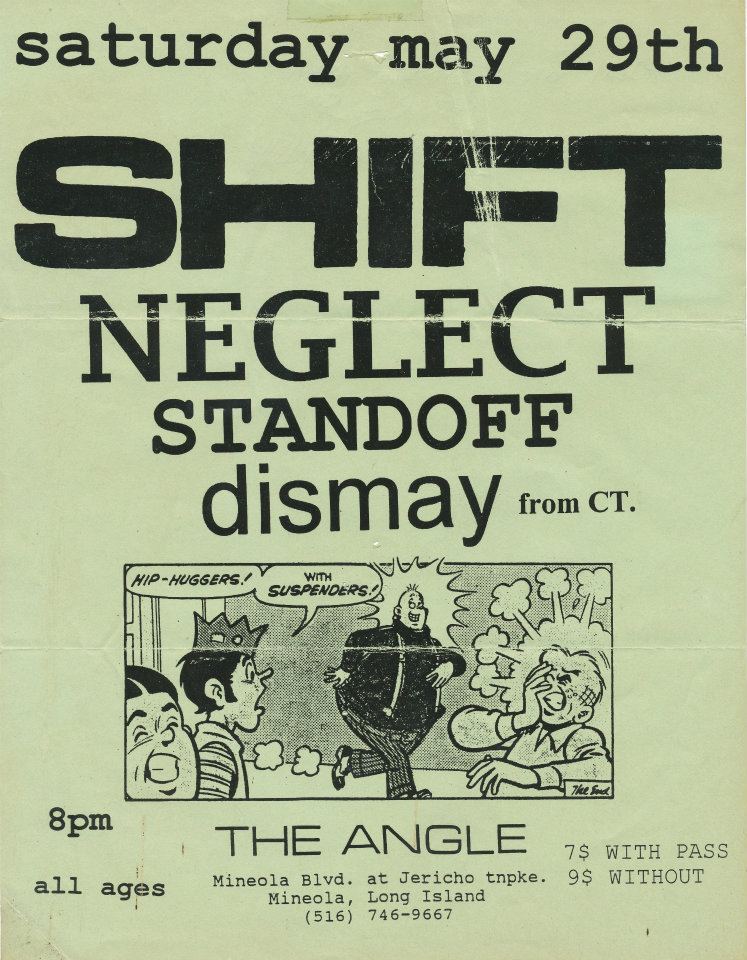

There was another magazine called Creem Presents Thrash Metal — and they would sometimes cover crossover and hardcore bands like the Cro-Mags, DRI, Bad Brains, Sick of It All, Agnostic Front, Murphy’s Law. I started getting really into all those bands — then that led me to Gorilla Biscuits and Judge and then Supertouch, Quicksand, and Burn. I was scared to go to the shows for a while because I’d heard they were violent and that you could get beaten up for having long hair — which I still had at the time. Plus, you had to be 16 to get into the Ritz or CBGBs. I think the first hardcore show I went to was one of the Superbowl of Hardcore shows at the Ritz (which had moved uptown at that point) in 1991 (with Agnostic Front, Gorilla Biscuits, Sick of It All, Supertouch, Vision, etc.). I was a few months shy of turning 16 but I just decided to give it a shot and they didn’t ask for ID. That pit scared the shit out of me.

Did you play in any bands before Shift?

Shift was my first band. We started in freshman year of high school. We would rehearse in our original drummer Jonny’s house on the 22nd floor of an apartment building in Chelsea. We started out by playing a weird mix of cover songs; Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, U2, Biohazard, Leeway. Then we started writing our own songs and playing talent shows at my high school.

How did you first meet Samantha Maloney and Brandon Simpson, your bandmates in what would become Shift?

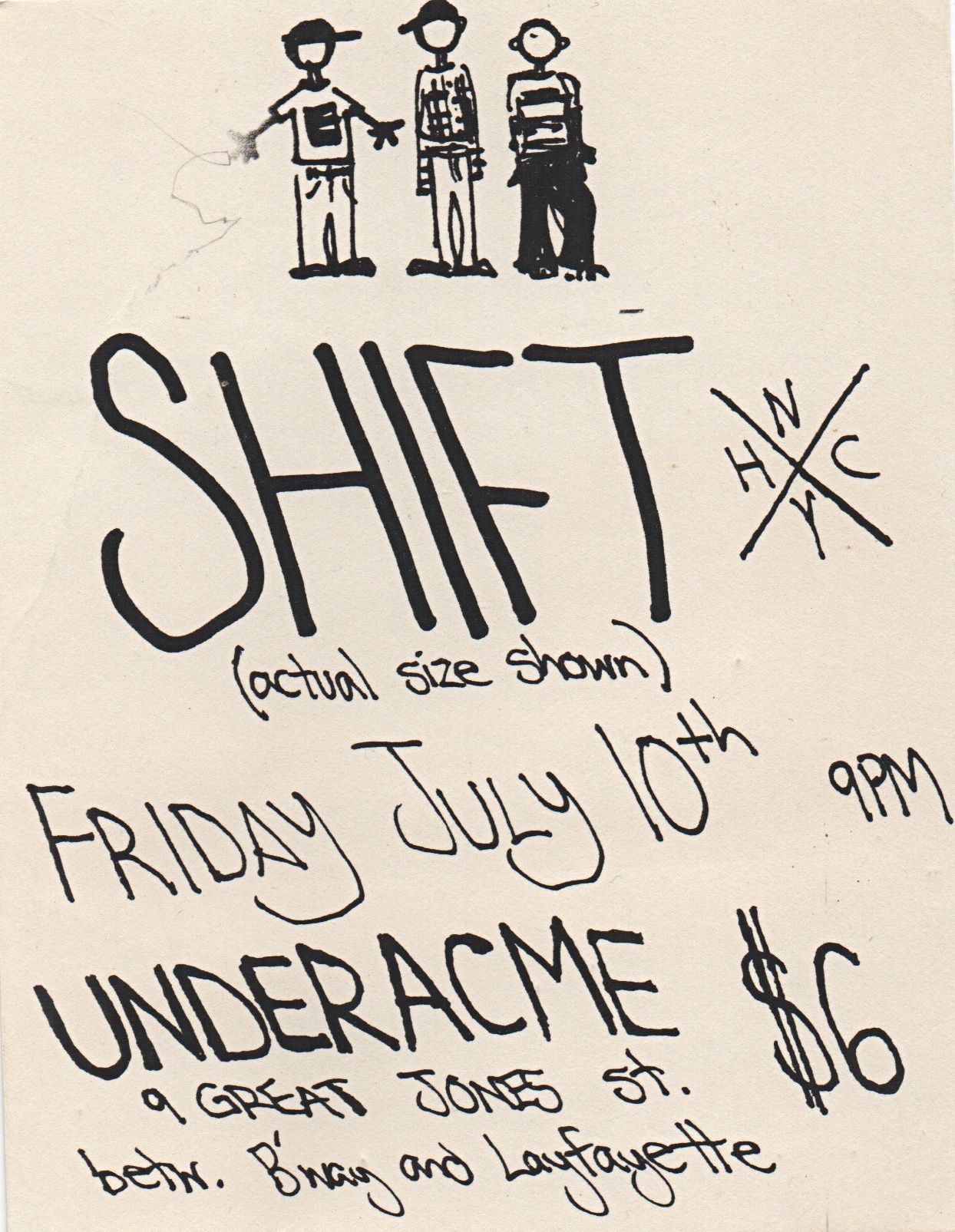

I met our original drummer, Jonny, first because we went to high school together. We needed a bass player and Jonny’s friend recommended Brandon who went to a different school. He liked Metallica and was hilarious and we hit it off right away. Then Jonny was going away for the summer and we got an opportunity to play a show at an actual club — a place called Under Acme. I can’t remember where that opportunity came from, but it was a big deal to us — so we decided we couldn’t pass it up and we needed to find someone to fill in on drums. My girlfriend at the time (Ida Pearle — who did the cover artwork for Pathos and Spacesuit — not to mention the back cover of Into Another’s Ignaurus) said there was a girl who played in her school’s orchestra who was really good. We tried her out and it definitely clicked. We played the show and we thought it went really well and we decided we would tell Jonny he was out and Samantha was in.

What did you guys set out to do, musically speaking?

Our influences were all over the place, so we were definitely trying to figure out what kind of band we wanted to be. At the beginning we were sort of torn between the NYHC tough guy vibe (even though we were not tough) and the more emo thing. I think that’s one of the reasons I loved Burn. They were aggressive and sort of intimidating but also musically and lyrically really interesting. Even though we didn’t really sound like Burn, they were a huge influence on us. They were one of the bands that showed me you could be in the NY hardcore scene but still push boundaries and do something that had a lot of other layers to it. Quicksand, Supertouch and Into Another were really big for us too — I loved all of those records so much.

Tell me about that 1993 demo. You guys were still in high school when you recorded it, right?

I guess we recorded it during my last year of high school. Brandon was a year older than me and Samantha a year younger. I can’t remember how we found the recording studio, but it was a guy named Jay Wasco who had a studio somewhere in Chelsea or midtown or something. We didn’t know what the hell we were doing but we were psyched just to be doing it. I remember listening back to the tape and I just couldn’t believe I had a real recording of these songs we wrote. Our friend Bryan Livov (who was in a band called Blindside) drew a graffiti-style logo for us. We got tapes made and Brandon and I typed out the liner notes and made the booklets ourselves at the copy shop and folded each one and put them into the cassette cases, and then took them down to Bleecker Bob’s and asked them to sell them on consignment. They had a big glass case of demos for sale that we would always look through. That was a huge moment for me — seeing our cassette tape under that glass. Like, “holy shit, I’m in a real band!”

That same year you released the Turnbuckle cassette. Did you consider that an EP, or did you guys view it more like a demo?

We were still thinking of it as a demo. The goal was for it to lead to us getting onto a label. It’s funny, I actually forgot that it was the same year as the first demo. Things develop so quickly when you’re young and I feel like we grew a lot between those two demos and really started to figure out our sound. On the first demo, we still had one foot in that NYHC crossover style – “Bumrush” was definitely heavily influenced by Leeway’s “Rise and Fall.”

But for Turnbuckle, we were more influenced by Quicksand and Burn, who were basically creating the genre of “post-hardcore” at the time, as far as I’m concerned. It’s funny since I ended up playing with him later, but Gavin’s guitar playing in Burn and Die 116 was a really big influence on my song-writing at that time. He was using some interesting chords — like 7th#9 chords — which I recognized from learning Jimi Hendrix songs (E7#9 is the main chord in “Purple Haze”) — or another chord that I love that I heard Gavin use was basically if you play an F# major chord on the 2nd fret — but leave the B and high E strings open and it just has this cool ringing quality (I think it’s sort of an F#11 chord, but I could be wrong).

If you listen to Burn’s “New Morality” and then listen to “No Avail” from “Turnbuckle” (and re-recorded for Pathos), you can probably hear how I was inspired by what he was doing — even though the songs are pretty different. I also used that chord in the main riff of “Pinprick” (on Spacesuit).

How was it working with Don Fury? He's such a huge part of the NYHC scene of the '80s and '90s.

We were in awe of him since we’d seen his name on so many great records, but he was really great to work with. He had a cool studio space that was in the basement under a storefront, so you would open the metal doors on the sidewalk and go down some stairs into this dark, dank space. It was a perfect vibe. He probably thought we were annoying kids who couldn’t play in time — although I bet he was pretty used to that. He was really nice to us though and held our hand through the process since we still didn’t know what we were doing.

You went with Don Fury again for your next release, the Pathos EP. That was one of the early albums released by Equal Vision Records, a label that has obviously gone on to become a powerhouse. How did you guys hook up with them?

I can’t remember how we first got in touch with Equal Vision — I have a vague memory of Steve Reddy, who owns the label, introducing himself to us at a show and saying he liked the band and wanted to talk to us. We were starting to get on some decent shows in NY, so our profile within the scene was rising. One of the people who was really amazing to us around that time was Roree Krevolin. She used to book shows at the Marquee on 22nd street and also managed Burn on and off. She took us under her wing and got us on shows and told other bands about us. She was a crucial part of our growth at that stage. Unfortunately, we sort of had a falling out a little later on — which I’m pretty sure was completely our fault. We were kids and didn’t know how to communicate.

So anyway, we also spoke to Doghouse and Wreck-age Records, but somehow Equal Vision just felt right to us. Steve was (and is) just a really down-to-earth, likeable guy. I guess it was weird because at that time they were essentially exclusively a Hare Krishna label — since they’d only put out Shelter, 108 and I think an album of devotional Krishna music. We loved Shelter and 108 and Steve said they wanted to expand beyond Krishna-related bands and we ended up being the first non-Krishna band on the label. It was a small operation at the time, and I even worked at the Equal Vision offices for a while; answering phones, packing up boxes of records and merch, etc. Steve and his wife Kate are really great people and I learned a lot from them. I have nothing but fond memories of our time with Equal Vision.

I think there’s a huge jump in quality from the earlier material to the six songs on Pathos.

I rarely listen to the records I made — and to be honest it’s weird to think about whether I’m happy with something I did over 20 years ago. The only logical way to think about the past is to say “that was the only record we could have made at that moment in our lives.” Once every couple years or so I’ll put on a Shift record and listen to most of it. It kind of just is what it is. There are always moments where I go “that’s a cool idea, I can’t believe I thought of that when I was 18” and others where I just cringe and say “I can’t believe I put that on a record and no one laughed in my face.”

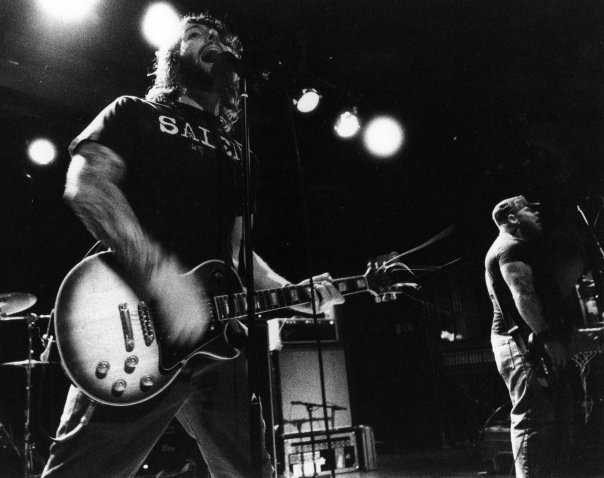

Were you guys touring a lot at that point? I saw you guys live quite a bit since I lived in the area, but I wasn’t sure if you got to hit the road.

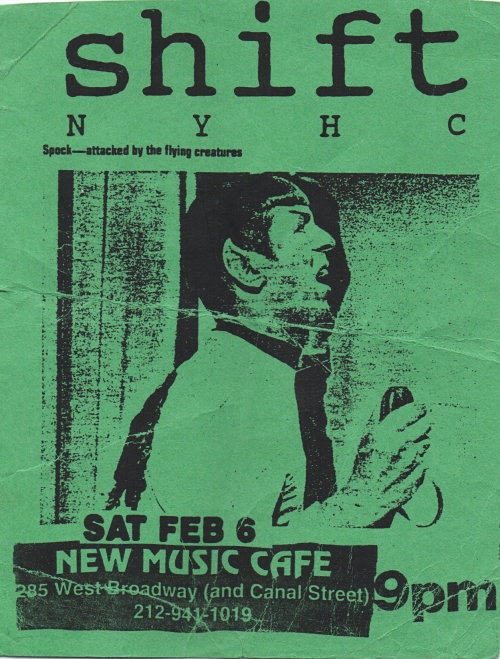

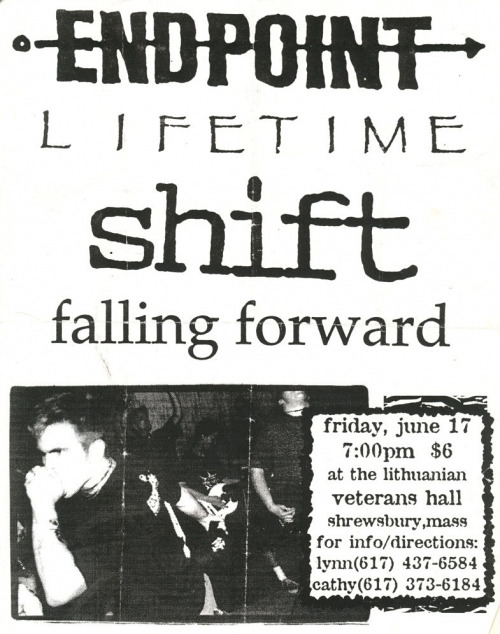

It’s funny how fuzzy my memory of some of the details are. We did our first real tour right before Pathos came out — that was with Endpoint and Falling Forward. Roree, who I was just mentioning, hooked that up for us, which in retrospect is pretty amazing, since we were touring around the country and no one outside of New York City knew who we were at that point. She went out on a limb to make that tour happen for us. I was a Manhattan kid so I didn’t even have a driver’s license at that point — I remember I had to rush to pass the test before the tour started. Samantha already had her license since she was from Queens! Brandon didn’t have a license so he got to sleep in the van most of the time on that tour.

After Pathos came out we mostly just did local shows and weekend trips around the east coast for while — Boston, New Haven, Philly, etc. And then just before Spacesuit came out in ’95, we started getting some good tours.

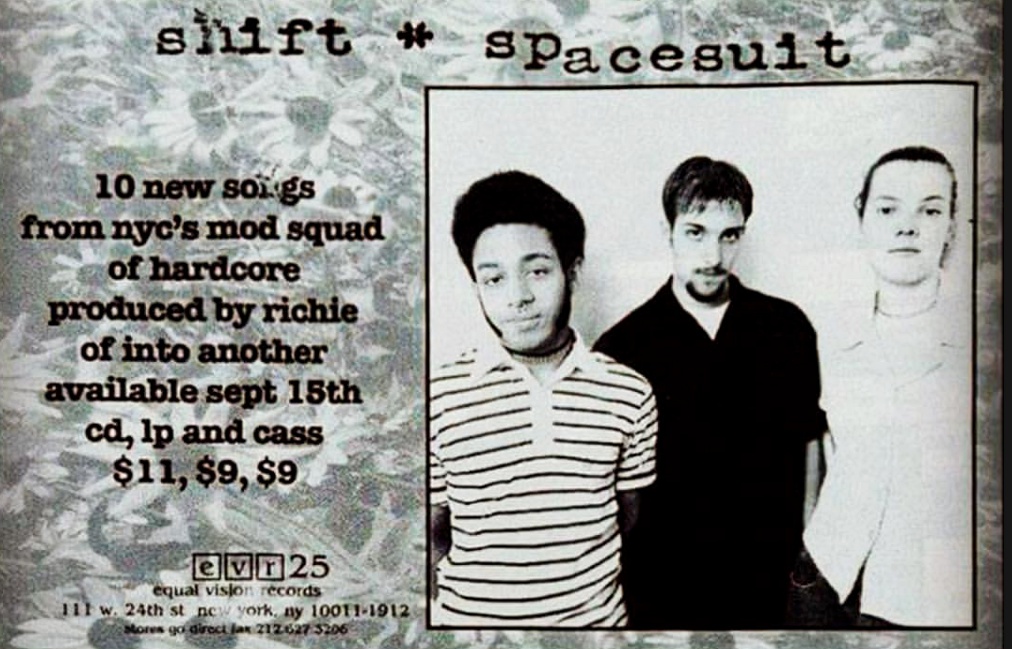

For your first full-length album, Spacesuit, you brought in Richie Birkenhead (Into Another, Underdog) to produce the sessions.

We were all huge fans of Into Another, so once again, we were just in awe of the situation. There was also an engineer named Ray Martin on those sessions who was great, and who helped us out a bunch of times over the years. Ray was behind the board and Richie was more about the big picture — helping us make decisions and get the best performances. This is another instance where someone helped us out and gave us a leg up. Just having Richie’s name on the record gave us a lot of legitimacy in the scene and I don’t think he got paid anything to do that. Ray probably got paid very little — so he deserves a huge thanks too!

I remember the songs “Pinprick” and “Spacesuit” getting a lot of airplay on WSOU. It felt like there was some momentum building for the band.

A lot of that momentum starting building just before Spacesuit came out. We were getting on better shows in NY and on the East Coast and then we got on a pretty amazing opportunity to tour with Clutch and Tad — “Amazing” to us in the sense that those were bands from different scenes than ours — the shows weren’t “hardcore shows.” That was hooked up by Tim Borror who was and still is a booking agent. He’s another person that helped us several times along the way. When you’re 20 years old and excited about your band it’s easy to accept help and say “thanks” but not really appreciate it on a deeper level. But looking back I realize how many people were generous and helpful along the way and made it possible for us to experience so many cool things. Around that time we also went out on tour with Into Another and with Orange 9mm. Those bands both hooked us up a lot.

We also toured Europe with Earth Crisis just before Spacesuit came out — which is sort of a crazy pairing but we had a blast. We were starting to play around with having a second guitar player — so we asked our good friend Manny Carrero (who played bass in Stillsuit and then later in Glassjaw, Burn, Saves the Day, etc.) if he would come along with us.

On that tour we actually played a show in Germany with Undertow, which was the first time we’d met those guys. Then after Spacesuit came out, we had a little period where Samantha quit the band. During that stretch we did a US tour with Texas Is the Reason with Ryan Murphy from Undertow playing drums. We also had a second guitar player on that tour — a guy named Justin Hogan. Then after that tour we talked Sam into re-joining the band. Justin left and we asked a different member of Undertow to be in the band — Mark Holcomb.

We liked having the ability to do more layers live and also just sound heavier. Plus we hit it off with Mark and he was coming at things from a slightly different angle — and was into a lot of bands I wasn’t hip to yet (like Drive Like Jehu, Pitchfork, Neurosis) so he added a lot to what we were doing.

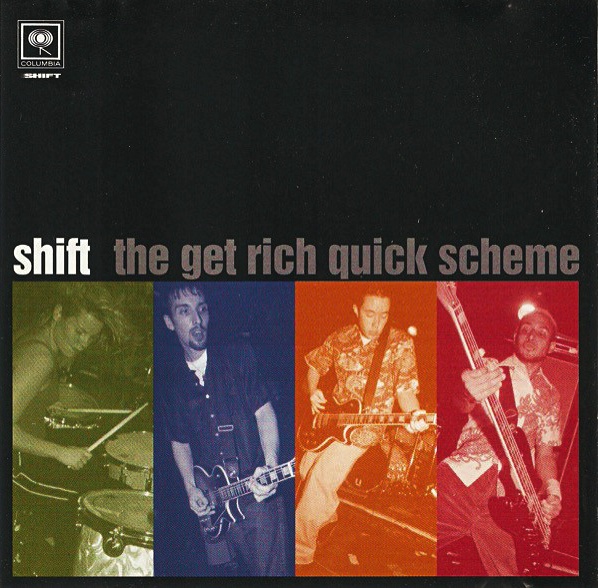

After Spacesuit, Shift signed with Columbia Records. Was that a case of an A&R coming after you, or did you have a manager who was shopping the band to suitors?

We didn’t have a manager at that point, but we had a lawyer named Richard Grabel — who was the lawyer for lot of great bands (Sonic Youth, Shudder to Think, Into Another and lots of others). He was getting A&R people to come out to our shows. Other New York “post-hardcore” bands had gotten signed (Into Another, Orange 9mm, Handsome) so there was a buzz about the scene. Columbia made an offer and we went for it.

I have to say, when I first heard that you had Clive Langer & Alan Winstanley producing your next album, Get In, I was very surprised. I knew them from their work with Elvis Costello and Morrissey, so imagining them working with a post-hardcore band was intriguing.

We met with some different producers, but I think ultimately our goal at that point was to be a “rock” band, not necessarily a post-hardcore band. I loved Elvis Costello and they had also produced the big Bush record (Sixteen Stone) — so I think part of it was trying to latch on to some of that modern rock radio magic. This may sound conceited, (and keep in mind, I was 21 years old at the time) — but I remember thinking that a lot of the other post-hardcore bands that got signed did records that sounded like post-hardcore records and we wanted to see if we could be something “bigger” or with broader appeal than that. I can look back and wonder if maybe we had stuck more to what got us to where we were, things could have turned out differently, but who knows. I also think that our concept of being a mainstream rock band was a fine idea — but maybe our songs didn’t quite back it up. Maybe if we’d made another record after Get In it would have started to come together.

Earlier in Shift’s career, the band was compared to Quicksand quite a bit, but the material on Get In was far-removed from that sound. How much of that change was informed by working with two producers that came from a completely different world?

I loved Quicksand and I think my voice had a similar quality to Walter’s, so it only made sense that we sounded like them. I’m not going to lie, at the beginning I was probably actively trying to make us sound like Quicksand, but I think we did have our own thing from the start as well. In some ways, I totally get why people said we ripped them off, and then in other ways I think that was inaccurate or at least simplistic.

There were some big differences in our songwriting styles — for example Quicksand songs rarely had a traditional chorus, whereas I think we did on a lot of songs. They also never did “ballads” — which we had on each record. Like “Dress Up” from Spacesuit. Quicksand didn’t really do stuff like that. I also was trying to push the emo-honesty lyrical thing really far. I used to write lyrics and think “if it makes me uncomfortable to say this then I definitely have to say it.” Richie and Into Another really influenced me in that way. He wrote a lot of really intensely personal stuff.

As far as Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley, they were great to work with — but they really just helped with the sounds and production and getting good takes out of us and didn’t have much to do with the songwriting.

Were you worried that the stylistic change would alienate your fans, and was the label on board for the change?

I think I was sick of the constraints of the hardcore, emo, and post-hardcore scenes and consciously wanted to bring some of the rock attitude of our favorite non-hardcore bands to what we did. I think I probably naively thought it was going to be so awesome, everyone would come along for the ride. But I also think I just wanted to stir shit up a little bit. Just having song-titles like “I Want to Be Rich” and “In Honor of Myself” was kind of a way of distancing ourselves from the introverted, shoegazing vibe of the sweater-vest-wearing emo scene. Also, those lyrics were supposed to be sort of provocative and a little tongue-in-cheek — but not everyone got the joke. The lyric in “I Want to Be Rich” is “I want to be rich and I want everyone to love me” –— I was trying to talk about vanity and vulnerability and how wanting to be a “rock star” is really just about wanting approval — sort of trying to be “meta” in the sense that this was our major label debut. But again — maybe that’s our fault for not quite nailing the trick we were trying to pull off.

It’s also funny because Walter’s band after Quicksand — World’s Fastest Car — had a song on their demo with the lyric, if I’m recalling correctly — “you want to be rich” — so people were saying I stole that from him too — but I swear, as far as I can remember, I hadn’t heard that song. I didn’t hear that demo until later and I don’t think I ever saw them play live. We may have actually played a show with them once but I have no memory of seeing their set. Who knows, maybe I did hear it and forgot and accidentally stole the line. I just remember being like “Fuck — I’m trying to move past being called a Quicksand rip-off and now I’m accidentally stealing Walter’s lyrics!”

Being the big Your Arsenal fan that I am, I have to ask you about former Morrissey drummer Spencer Cobrin’s involvement in the sessions since his name appears in the liner notes.

You are really hitting me with some in-depth questions. I haven’t thought about a lot of this in a long time. Clive and Alan had worked with Spencer on the Morrissey record and maybe some other records too so they asked him to come and add some programmed drums to the song “Numb.” It’s mostly just the first few seconds of that song. I guess it added a “cold” mechanical feel to the intro which made sense with the lyrics. I think it was Clive’s idea and we were open to pushing things in new directons. They invited Spencer to come down to the studio and he was very cool and down-to-earth.

Looking back, how would you sum up Shift’s time on Columbia? Do you regret signing with a major?

I don’t truly regret anything because that’s pointless — we were who we were at that point in our lives — but I certainly have a lot of things I would probably do differently if I could do it all over again. It may be not be like this now, but signing to a major is one of those things that is really hard to say “no” to. People are telling you “you could be a really big band” and it’s hard not to get caught up in the excitement. You think “yeah, maybe I am supposed to be a rock star. Maybe I really am Joe Elliot.” [Laughs] But in retrospect, we gave it a shot and it didn’t work, and it’s kind of as simple as that. Some of the reasons it didn’t work were our fault and some were other people’s faults and then there’s also just the fact that major labels put out a lot of records and if you don’t show them quickly that you’re going to make them a lot of money, they move on.

When and why did Shift break up?

Well, I don’t know if this is the answer the other band members would give you — but from my perspective (and hazy memory) — we weren’t getting along great for starters. There was some ego stuff, which was mostly just about being young and not knowing how to deal with conflict and mild adversity. And then Hole was looking for a drummer and Sam got asked to audition and ended up getting the gig. That put the rest of us in a position of either waiting around for her to have time off from Hole; replacing her; or breaking up. For some reason, we decided to break up — which now seems like the dumbest of the three options. I think we just had a bad taste in our mouths from the experience of the Get In record not going as we’d hoped — and I sort of arrogantly thought — “I don’t need her, I’ll just start a new band and it’ll immediately be just as big.” But I also could have started another band and kept Shift going too.

I guess I’d always made Shift the most important thing in the world — and I didn’t like the idea of it being on the back burner in any way and I didn’t like the idea of Shift being someone else’s “other” band. Now that seems kind of immature. I also think the major label stuff created some rifts — there was some tension about publishing and how decisions got made and stuff like that. Again, looking back, I was probably a bit full of myself and thought my vision for the band was more important than anyone else’s. I was the de facto “leader” of the band but I wasn’t good at dealing with conflict so I tended to be passive aggressive and would keep things bottled up. All of that didn’t help when things didn’t go as planned.

After Shift broke up, you formed a new band called Big Collapse. Sonically, Big Collapse had more in common with your earlier songwriting.

I’m not sure I agree that it sounded like the earlier Shift stuff — but you might be right. I thought I was trying to do another variation on the theme of Get In — rock with some post-hardcore elements in it. I met Matt Kane through Ray Martin (who I mentioned was the engineer on Spacesuit) and he turned out to be a great guitar player. He thought about playing guitar differently than I did and added a lot of stuff I never would have thought of playing. That comes through even more on the second record (Prototype).

You released the eponymous Big Collapse debut album on GrapeOS, a label co-founded by Scott Winegard of Texas Is the Reason. Was that a situation where you wanted to work with someone from the local scene after coming out of the major label thing?

GrapeOS was actually run by Scott Weingard and Dave Wolter — who was an A&R guy at Hollywood Records at the time, where he’d signed Into Another and Seaweed. This was like his side-project label that he was doing with Scott separate from Hollywood. I think I liked the idea that it was a small indie run by someone with connections in the major label world, and Scott and Dave were both friends of mine — so in that sense you’re right — it was like working with friends after working with a giant corporation. Dave Wolter is another person to add to the list of people who helped me out immeasurably without getting paid for it. Just a really smart, good guy who taught me a lot about how the industry worked. I probably should have been paying him as a therapist since I talked his ear off endlessly during the Get In time with Shift — complaining about band dynamics and the label and the management and the booking agent.

Before the second Big Collapse album, Prototype, Gavin Van Vlack (Burn, Absolution, Die 116) joined the fold.

So, pretty shortly after the first Big Collapse record came out, Matt and I started discussing the idea of moving to LA. We had done one tour as Big Collapse — touring with the band Joshua across Canada and back across the US. The lineup for that tour was me and Matt plus Chad Dziewior (Threadbare, Tiers) on bass and Joe Gorelick (Garden Variety, Blue Tip, Retisonic) on drums — both of whom hadn’t played on the record. The lineup was great but the tour ended up being a nightmare. It was basically booked by me and Dan Coutant from Joshua. Everyone was cool, but the tour was just very poorly attended and ultimately a total bummer. Coming off of Shift breaking up and finally getting a new band together and going on our first tour and having it suck was sort of a gut punch.

Then the last show on that tour was in Syracuse (or maybe it was Buffalo) on September 9th, 2001. We drove home after the show and got home on the morning of the 10th and the next day 9/11 happened. I think all of that made me re-evaluate everything in my life. I started thinking about the idea of shaking things up and trying something new. Matt was into the idea too, so we packed up our stuff and drove a rental truck to LA. I wasn’t trying to run away from NY — it’s more that 9/11 put things in perspective and you only live once and I wanted to do something exciting and drastic.

I don’t think Chad or Joe really wanted to be in the band anyway, so Matt and I said we would try it in LA. Pretty soon after moving out there, I ran into Gavin who had just moved out there as well. We were already friends and Shift had played lots of shows with all of his bands (Burn, Die 116 and Pry). He’s mainly a guitar player, but had played bass in Pry and in certain incarnations of Die 116. So we asked him to be in the band on bass. Then another friend named Pablo Mathiason recommended a drummer named Kyle Stevenson — who ended up as the new drummer. (And let’s add Pablo to the list of people who helped out a ton along the way).

I think Prototype is an underrated record. Why do you think it flew under the radar?

Thank you. Who knows why. There are a lot of bands and a lot of records and so many factors. Maybe we didn’t get on the right tours — so we didn’t get in front of the right people? That was 2003, 2004 — there was a lot of screamo and stuff like that going on. We played a lot of shows in front of those kind of kids and I don’t think they knew what to make of us.

We wanted to tour with other types of bands, but all of our connections were more in the hardcore world and the label (The Militia Group) was definitely in that world. Maybe if we’d done another record, things would have been different. We had a great management company — Vaughn Lewis and Kenny Gabor at Strong Management (Killswitch Engage, As I Lay Dying) — who went way, way above and beyond for us. They’re still close friends of mine and I consider them my brothers forever.

That brings me to Kodiak, a project you started that didn’t get past the demoing phase.

After Prototype came out, we toured a ton. We just got in the van and drove around North America for about a year. It was rough and it really put a strain on our friendships. Gavin decided he was going to quit and move back to NY. We kept going for a little bit and then Matt decided he wanted to move back to NY too, so Kyle and I decided to start a new band. We demoed some songs and played a few shows, but I was just really burnt out. I just needed to not be in a band for a while — and then that “while” turned into the last 12 years or so. I think I lost the fire that I used to have for that life. I used to wake up in the morning with a list of things I wanted to do for my band — and I started to not feel that way anymore, which seemed like a sign. If you’re not going to put 110% into then it’s just a hobby — and being in a band as a hobby doesn’t excite me for some reason.

Would you be open to having the material officially released?

I think we had some good songs, but they never got developed enough. Not sure what the point of releasing them would be.

These days, you compose for television and film. How did you get into that world? Since I work in television, I know it’s extremely hard to get a foot in the door.

I mostly do music for commercials. I had a friend who was doing it and he kind of showed me the ropes (another great guy -— Greg Griffith — who used to be in a NY band called Vitapup). He gave me an idea of what the job entailed, and then I just literally cold-called a ton of music houses (which are companies that work with ad agencies to provide music for commercials) and got a few bites and then kept doing it and got more contacts until it was generating enough money for it to be my full-time job. I’ve been doing it full-time now for about 9 years. I work from home, writing music and recording it on my computer. It’s not a bad way to make a living. I’m not in Def Leppard, but I do get paid to make music and I also get to be home with my wife and our two kids instead of living in a van.

Do you see yourself ever starting a band again?

Probably not. I may record some music for fun and “put it out” — whatever that means these days — but who knows. The idea of doing music for a movie or TV show that I really like is honestly much more exciting to me.

Thinking back to Shift, what are you most proud of?

Probably just how much energy and effort I put into it — and that it paid off to the extent that it did. Brandon and I used to stay up all night making flyers at this 24-hour copy shop on 11th street. Then we would hand-write hundreds of names from our mailing list onto the cards and put stamps on each one and mail them out. Then walk around to every record store and every show handing out flyers. We were full of youthful optimism and believed in the band and really wanted to get people to listen to us.

Would you be open to a Shift reunion?

In a general sense, I guess the answer is yes. It’s been brought up a few times, but we all live in different cities now. Samantha and I both live in LA; Brandon’s in NY and Mark is back in Seattle. Ultimately, if we were going to do it, I would want it to be really good — which would mean we would need to rehearse — and since we all live in different cities and have busy lives, that is sort of complicated. I wouldn’t want to play and be disappointing and tarnish people’s view of us. I’d rather that the people who liked the band have a perfect, shiny memory from a long time ago –— than for us to be mediocre and sloppy and have them go “hmm, maybe they were never that good. What was I thinking?”

Also, for whatever reason, I think Shift has been sort of forgotten by history. Some bands seemed to grow in stature over the years — Texas is the Reason is a good example — but that doesn’t seem to have happened for Shift, but I’m totally okay with that. It was an important part of my life and I’m grateful I got to experience it.

***

Check out Josh's website to sample more of his composer work.

Tagged: big collapse, kodiak, shift