The story of modern New York City, as I'm sure you've heard, is one of crushing affluence and paved over oppression. For decades now, urban renewal projects have targeted the slums of yesteryear for redevelopment.

Projects fueled by investment bankers looking for safe bets in which to anchor growing fortunes—welcomed by capricious politicians looking to address real issues of crime and poverty, with policies that appeal to suburbanites who only ever entered the City for work, or to take their bitter and bored kids shopping at Bloomingdale's.

Every solution proposed, treats the inhabitants of those neighborhoods targeted for "revitalization" like they were weeds. Tolerated only so long as they could not be permanently removed. The justification being that any new development is good for the City's economy.

It creates jobs (if only temporarily) and attracts amenities, while sprucing things up and making them attractive to tourists and high-income earners looking to put down roots (for six to eight months at a time). The people who are displaced can simply find somewhere else to live. They weren't making best use of the area's potential, anyway.

These modern justifications for gentrification are not that far a cry from the justifications for locking people up or evicting them in the '70s or '80s. Only in those decades, there was an implication of criminality foisted on the urban poor, which is more subtly implied in the discourse of today.

However, you didn't have to have lived through those decades to know what people outside of New York thought of the people who lived in it. TV and movies of that era are more than ready to serve as a window into the collective consciousness of the past. At one point, there was a sense that the City was a wasteland, a maze or ruins, or a poorly managed, open-air asylum.

These nightmarish impressions permeated much of the pop culture towards the latter half of the 20th Century. John Carpenter visualized the depths of the public's phobia towards urban environments and projected back at the viewer all of their vicious delusions and derangements, most notably and successfully in Escape from New York. While earlier films like Michael Winners' Death Wish imagined urban spaces as dark physic playgrounds, where ostensibly civilized men could act out raw fantasies of violence under the guise of revenge and justice.

Both of these films remain popular, and seem to resonate with audiences to this day. Despite the successes of gentrifying influences on many of the boroughs, specifically, Brooklyn and Manhattan, there remains a sense that the old, violent nature of the City still skulks in its shadows. These fears continue to result in calls for ever-larger expenditures for police, cuts to public assistance, dismantling of public housing, and proposed renovations to make neighborhoods friendlier to tourists and day-working professionals.

But, something funny happened when COVID hit NYC and other urban centers this past year. Suddenly, wealthy tech and knowledge workers no longer had a reason to commute downtown. Their routines shifted from catching a train from their $3.5k a month apartment to what ever converted factory spaces they designed sneaker ads or managed cryptocurrency exchanges in, to a more relaxed schedule that consisted of shifting from the bed, to a laptop on the kitchen table, to their sectional in front of the TV, and back to bed.

This routine doesn't require you to maintain a residence in the City proper, let alone one that you pay an extortive amount of money for in order to live near the right bars and gallery spaces. So, a lot of them left. They either went home to live with their folks, or bought a nice big home in the exurbs.

And in the blink of an eye, less than a year in total elapsed time, the conversation for many has returned to questions of urban blight, of streets empty but for drug addicts and muggers, and of the need for tourists, when they dare to enter the ailing City, to walk swiftly and avoid eye contact with strangers.

As it turns out, the old New York never did go away. It was always there, in the blinkered imagination of the public, who need something and someone external to them to fear, in order to justify their lifestyles of isolation and self-gratifying consumption.

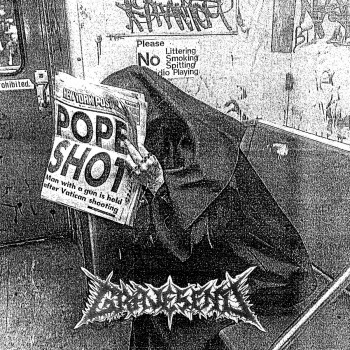

Stepping onto the psychic plateau of exteriorize anxieties and dread, and seizing hold of its nightmare logic, to bend it towards a point of culmination, is the NYC death-grind band, Gravesend.

Named for a grisly sounding, but relatively placid neighborhood in Brooklyn, the group captures a gripping sense of terror, similar to that which twists and knots the bowels, and ices over the heart valves, of middle-class parents when they read up on the crime statistics of the neighborhood on the opposite side of the street from their progeny's art school dorm.

There is a savagery, without hesitation, conscience, or illusions of morality, exhibited by the band on their debut album for 20 Buck Spin, Methods of Human Disposal. A clash of a pure unrepentant instinct against the cowardly and puerile cognitive defenses of a sheltered and cloistered citizenry.

With the colonizing project of urban spaces ground to a halt at present, the legacy of empty offices and a restless police state has never been more apparent. The real terror, though, is not what is left behind but what will be done to protect it. Gravesend's Methods of Human Disposal is a presaging of the ways in which the powers at be will converge to preserve their investments and make sure that everyone stays right where they belong in the food chain.

If you need backhanded clues that the album operates as PSA, a warning of the present and future war against the poor, you need to look no further than the second song on the album. "STH-10" is literally a kind of air-raid siren. A warning system, meant to alert you to the storm to come.

With a ricocheting death growl, a sputtering cry that hooks you by your nose hairs and drags across the concrete, it will leave you feeling tender and susceptible to the bruising title track that follows.

The sky ripping, guttural melodies of the album's title track are like a blaze in the northern sky, a forerunner of the incoming hail of fire that will be blanketing your ears like sand at the base of an hourglass.

If you didn't realize your time was up by now, then the gnawing, chew and churn of "Ashen Piles of the Incinerated" will disabuse you of this diluted notion, with its boiling hot, tar-baked grooves, jagged-edged guitar swipes, and hate-gargling, reptilian vocal snarls.

The band's training in the ways of Bolt Thrower is obvious on the hitherto mentioned track, as it is on the stone-heeled march and crater-junction pummel of "Trinity Burning" and the canon volley tear and suicide charge of "Subterranean Solitude."

There is no denying the creeping influence of Obituary's maniacal thrash shiver on the latter track, as well. The band's punker influences become evident on the upper-cutting pit-breaker and blackened hardcore scrape of "Scum Breeds Scum," and moreover on the demonic, bullwhip thrash of "Absolute Filth."

There is a crusty Wolvehammer devouring Darktrhone quality to a lot of what Gravesend offers, but they also have a tendency to breakdown resistance with gruesome Incantation-esque grooves, that very often, feel too big for the scuffed and flaky production quality to properly contain.

In my opinion, if you put something that pugilist in your black metal, it's not black metal anymore. It just has too much of a will to survive.

It's to the band's credit that they are able to maintain such a consistent sense of tension throughout their debut, and this is attributable to the clear care that went into building out each of these tracks. As an example, what starts out feeling like a cathartic exhale on "Unclaimed Remains" by its conclusion feels like a brutal constriction, carried out to its final anaerobic end by a wheezing peel of feedback.

Similarly, the samples deployed in the drug-den dredging "Needle Park" do almost nothing to decouple you from its frenzied tow through broken glass and gut ripping grooves, or the paralizing feeling that a venomous forked tongue is slowly curling over the outer lobe of your ear. There really isn't any point where you're not going to feel prickly or nervous while listening to Methods of Human Disposal.

I'd be willing to wager the value of a condo in Williamsburg, that this is exactly how the band intended you to feel while listening to their record. If you don't believe that you're being savaged within an inch of your life while this thing is on, then you probably are not listening to the right record (or at least not at the proper volume).

Methods of Human Disposal is as nasty and vile of an album the conditions that spawned it. New York may be hemorrhaging yuppies now, but that's no reason to believe that banks and politicians, and those whose treasures they promote and safeguard, will ever let the people there be self-determining. There just is not profit in the rebuilding of communities that will allow people to survive and thrive there.

Further, the fear of the people who would make up those communities, and what they might do with their power, is too great to ever allow such an insurgency of mutual aid to materialize.

Therefore, the future of New York, like the future of most American cities, from Chicago to San Francisco and back, will continue to look like a one-sided war to preserve empty buildings and vacant streets. A campaign to maintain a thriving necropolis, perpetuated by ever more clever and innovative measures of human displacement, and disposal.

Get It

- 20 Buck Spin (LP, CD, cassette)

- Bandcamp (Digital)

Tagged: gravesend