I’m not certain whether the responsibility lies primarily with the crust punks, straight edgers or Hare Krishnas, but between them all, a lot of attention has been paid to the topic of animal consciousness; more specifically, animal rights, and the lack of desire to consume them.

Even a handful of heavy metal bands entered the conversation, highlighting the issue of animal testing and vivisection:

"What have I done to deserve this? Give up your cruel practices." - Nuclear Assault, “Surgery”

Sure, those of us with pets in our homes love them with all our heart, but often, the relationship and discussion ends there. Be that as it may, there are many who've grown up as purveyors of aggressive music who have chosen to take their love and respect for animals to another level.

Albany hardcore fan, show promoter, artist attorney and all-around good guy Dave Stein comes to mind as an individual who wore his adoration for all creatures on his sleeve, tattooed and otherwise. The gentleman dedicated much of his time and energy toward raising funds and supporting causes beneficial to the four-legged and otherwise.

Sadly, Dave passed away recently after an extensive battle with illness. Posthumously, his family asked that anyone interested in honoring his memory consider donating specifically to Tamerlaine Sanctuary & Preserve located in Montague, New Jersey; co-founded by Queens, New York hardcore kid Peter Nussbaum and his wife Gabrielle Stubbert.

Why Tamerlaine? No Echo decided to look deeper into the mission of this sanctuary which Dave Stein was so fond of by chatting with the Tamerlaine co-head-honcho to get the 411.

Why don't we start by talking about your upbringing a little bit; where you grew up and what that looked like.

Peter Nussbaum: I grew up in Queens, in Fresh Meadows. A nice, pretty normal, relatively uneventful childhood. For some reason, the apartment complex I lived in didn’t allow you to have dogs. I’m not sure why dogs were singled-out, but we weren’t allowed to have them.

I do remember having guinea pigs and cats in our apartment though, probably beginning when I was around 10-years-old. My parents weren't into our pets at all. It was me and my sister who were more into having pets.

How did you get into music, more specifically, heavy, aggressive music?

I always loved music and was really into New Wave and some punk rock, unlike a lot of my friends who had already found much more aggressive music. The trajectory for those around me was usually metal into hardcore. I liked metal early on as well, but I really liked bands like Devo, and the Buzzcocks, The Clash and the Ramones. Those were the bands I liked in junior high school.

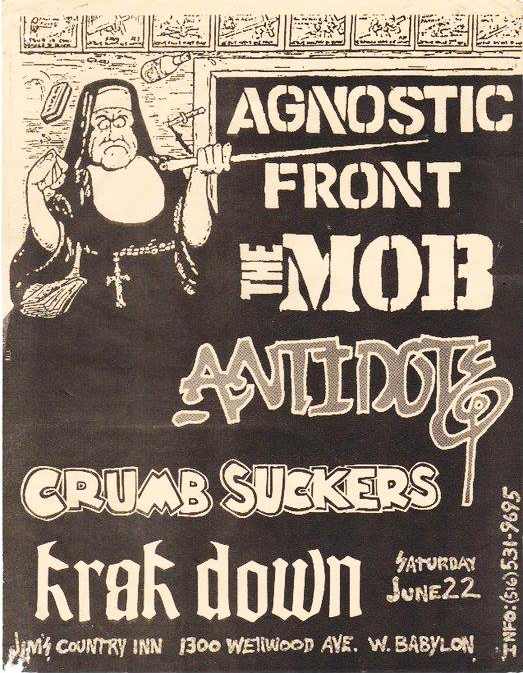

Then it sort of transitioned to the heavier stuff: thrash metal and mostly hardcore. In fact, I think the guy who's interviewing me right now might've been responsible for leading me to my first hardcore show. I don't remember exactly which show was the first, but pretty much my whole high school hardcore experience was with you by my side. I remember going to places like Jim's Country Inn out on Long Island to see Agnostic Front, the Crumbsuckers, and Krakdown.

And I remember lots of CBGB matinees. You were the ride for one thing, but we obviously shared great taste in music. It wasn't only the hardcore stuff either. I remember you turning me on to bands like Exodus and Nuclear Assault and other great, really heavy, aggressive metal as well.

Do you remember at what point you decided you wanted to become an attorney?

Yeah, it was in college. I had no real aspirations to go into lawyering until I think my senior or junior year of college. I went to school up in Buffalo and was having a really good time, so I had to figure out a way to stay there. I simply wanted to hang out in Buffalo for a few more years. That was really the sole determining factor, so I applied to the law school there; went to law school and really liked it. Here I am 35 years later.

I do intellectual property law, mostly trademark and copyright law, and a lot of it is related to music. I represent a lot of artists, record labels, publishing and merchandise companies in connection with their trademark and copyright related issues. I've represented a lot of the Roadrunner Records bands. I hit it off with the in-house people and started doing trademark work for many of their bands. It all blossomed from there. So, Machine Head, Slipknot, Soulfly, Sepultura; that's sort of where it started.

I've also done work for plenty of hardcore bands over the years like Shelter, Sick of It All, Vision of Disorder... The funny thing is, most hardcore bands aren't thinking so much about trademarks, but I've helped out a number of them.

I worked over the years quite a bit with Dave Stein, who we recently lost. I helped Dave out a lot with trademark and copyright issues for the hardcore bands he represented.

How did you and Dave Stein initially link up to work together?

It's a pretty wild story. I knew Dave a bit from the hardcore scene, and then, when I came back to New York City after law school, my first job involved litigation where Dave's firm at the time was on the other side. I was simply instructed to go over to the other law firm to talk to an attorney who was going to download some agreements onto a CD-ROM which were part of this case we were working on together, but on opposite sides.

When I walked into his office, I saw Agnostic Front and other hardcore band stuff on his credenza and on the shelves. I did a double take as I wasn't expecting that, mostly because it was a pretty fancy New York City law firm. I said, “Wait, you're into Agnostic Front?” We made the connection and became fast friends from there. We often bounced stuff off of one another and had worked together since then. Actually, the first vegan restaurant I ever went to was with Dave Stein.

What did it mean to you to find out that his family asked his friends and colleagues to do whatever they could to benefit your sanctuary in his memory?

Of course, it meant a lot. Dave was such a special human on so many levels. He cared so much about the bands that he worked for, and cared so much about social justice and he was a vegan way before I even thought about becoming vegan. Veganism was something I knew about because my sister's been vegan for 35 years, and other people in the music scene and the hardcore scene that we were friends with were too.

Dave and I had this bond where we would talk about everything and often. One thing he was particularly passionate about his entire life was injustice towards animals perpetrated by humans, so I knew he loved what we did up at Tamerlane. It was incredibly humbling when I found out from his family that they chose our sanctuary as a beneficiary of donations on behalf of Dave. It was humbling to say the least.

So how exactly does an intellectual property attorney come to build an animal sanctuary?

So, I was living in the city, and working in New Jersey about 23, 24 years ago. My father was put into a nursing home in close proximity to where Tamerlaine is. We were traveling from our apartment in lower Manhattan to see my father every weekend, and my wife, who grew up in Manhattan, desperately wanted to get a weekend place out in the country.

I was perfectly fine staying in New York City, but she convinced me that since we were going up to visit my father every weekend anyway, we might as well get a place so we could see him on the way up on Friday and on the way down on Sunday. I was sold, and we bought a farm in 2001.

At the time, we hadn’t become vegan yet, but we loved animals every bit as much as we do now. That's what I always tell people who aren't vegan. I don't judge non-vegans because I know that everybody loves animals. The thought of hunting was so abhorrent, but I ate animals, and was able to let the cognitive dissonance rule my existence.

It's easy to put up defense mechanisms and not think much about farm animals, but at a certain point while up there, we became vegan. Not too long after, we were like, wait a second, we've got these 40 acres of farmland, we could rescue some animals. That's how Tamerlaine started.

We started very innocently by rescuing two roosters from another sanctuary that friends of ours founded. They needed to make room because they were doing a big rescue and had these two roosters named Yuri and Jupiter that didn't get along with any of the other animals. They asked us if we would take them in. We had a garden, so we bought a coop and fell in love with those two roosters.

We quickly recognized that they were no different than our beloved dogs. It was such a profound experience for us. I mean, they would jump up on our laps; they would come into the house and eat breakfast with our two dogs. They would snuggle with the dogs in their dog beds. They were simply no different to us, so we decided we had to share the experience with other people.

We opened up our farm to the concept of taking in other animals, and once we were willing to take in other animals, the floodgates opened. Chickens in particular are the number one discarded farm animal. And when people found out that there were two vegan people with a farm willing to take in chickens, the phone was literally ringing off the hook. Taking in a couple of roosters was the gateway drug to starting an animal sanctuary.

What types, and how many animals are cared for at Tamerlaine?

We have about 290 animals at the farm at last count. It ranges, but right now, we have 7 cows, 22 pigs, 45 goats, 4 sheep. 2 donkeys, some turkeys, a lot of ducks and geese, some rabbits and a lot of chickens.

Which are the most challenging to take care of?

The chickens by far, which seems counterintuitive because they're small. Cows are actually much easier to care for than chickens. Chickens have all the cards stacked against them based upon the way that they've been bred for animal agriculture. The meat breed chickens have been bred to get so big so quickly, that all the things needed for longevity have been bred out of them.

They don't have a long-expected lifespan, so keeping them healthy and happy and giving them longevity is the most challenging thing that our staff confronts, yet we've managed to figure it out. We have chickens, meat breed chickens, that we rescued in 2014 which are still alive.

The layer breed chickens are very difficult to take care of for other reasons. They've been bred to lay so many eggs for the egg producing farms to be profitable. The eggs that people buy in supermarkets come from hens who are laying 350 eggs a year. All these hens descend from wild chickens, which were only created in nature to lay 8 to 12 eggs a year, and it takes a huge toll on their body. Those layer hens almost all succumb to reproductive cancer eventually.

And so caring for them, and dealing with the health issues that they have built into them from being these, basically egg laying machines, is really difficult. But there are unique challenges caring for all the animals. The animals we rescue all come to us from situations of abuse, abandonment, neglect, exploitation... A lot of them come to us with pre-existing problems, so much of our work goes into not only rehabilitating these animals, but giving them the healthiest, happiest and longest life possible.

So, many, if not most of them, are ultimately bred to become food for humans?

For instance, with chickens, their bodies are worth a dollar a piece to the poultry farmers. It's just basic economics. You must grow them to slaughter size in a short enough period of time so that the feed costs are not going to exceed a dollar. It's a volume business. So, the poultry farmers, they're doing tens-of-thousands of these meat chickens at a time, making pennies on the dollar.

All the meat chickens that are consumed in this country, their slaughter age is only 42 days, which is shocking to people. And by all accounts, the ones that aren't slaughtered at 42 days, with proper care, the expectations are that they can live for a couple of years. We found that they can live much longer if given great care. But of the billions of meat breed chickens, which are called Cornish cross chickens, the only place you'll see them alive past 42 days is at an animal sanctuary. Nobody else is keeping them alive past their slaughter age.

How would you explain the difference between an animal farm and an animal sanctuary?

Well, at an animal farm, they're using the animals for any number of things. They're either growing them for meat, or they are using them for eggs or for dairy, usually a combination. So that's an animal farm. At an animal sanctuary, the animals aren't being used for anything. The animals are just rescued, and their sole job is to live out their best life. The staff of a sanctuary; their job is to give the animals the care and enrichment they deserve. And if the sanctuary is doing it right, as we believe we are, we not only rescue and care for these animals, but just as importantly, we do our best to educate people about their plight and give people an opportunity to meet them and see that they really, truly are no different than people's beloved cats and dogs.

The joy of my life is doing tours at the sanctuary. I'm going all weekend long bringing in groups of people who get to meet the animals. And most of the people that come through aren't vegan. I see it firsthand every weekend; these people making the connection, like, wow, they truly are no different than my beloved dogs or cats, or bunny rabbits, or hamsters or whatever people have.

What was it that made you turn the corner and become a vegan?

My younger sister became vegan in high school, and I was the jerk brother who used to wave hotdogs and hamburgers in her face and give her a hard time about the crap that she was eating, because 35 years ago, plant-based food truly was crap. I mean, vegan food has come a long way. You give up nothing as far as taste or variety. I think most people know that by now. There are so many vegan restaurants, and there's even great vegan junk food.

For a lot of people, the trajectory is they eat some meat, then they give up certain meats; they switch over to being vegetarian, and then they realize that eating dairy and eggs, from an ethical standpoint, is even worse than eating meat. That's the typical trajectory. My story goes like this: I binged on a shit ton of meat at a charity event I attended. It was at a hotel in the city, for a food industry organization.

Every fancy, famous big-name chef had a station set up in this big ballroom, and people were just trying to devour everything they could. I was right there with them, eating Anthony Bourdain's creations, you name it. And I just devoured so much stuff. I’ll never forget the gluttony of it. I got on the subway in midtown heading back downtown and I just felt physically ill. I felt spiritually ill.

And I said to myself, “That's it. I'm done. I'm vegan when I wake up tomorrow morning.” I got home and my wife Gabrielle, who's the co-founder of the Sanctuary, asked how the event was. I said, “I am done!” I told her, “I'm vegan when I wake up tomorrow morning.” She said, “Yeah, right.” And she’d been vegetarian for a long time but wasn’t at that moment. She’d gone from vegetarian back to eating meat for a bit. I woke up the next morning and that was it. I haven't looked back. And that was I think 2008 or 2009, somewhere in there.

So you had the sanctuary for a few years before you became vegan?

Well, we already had our house that we first got while visiting my father back in 2002, that's still our house. That's a 40-acre farm. That's where we live, and we started the sanctuary there. But in 2018, we moved. We had the great fortune of being able to move to the adjoining farm, which is 350 acres. It's this incredible, historic property, and the house on this farm was built in 1774.

We became the third owner. It was actually a stop on the Underground Railroad. It’s just this beautiful, majestic place, and I never thought in a million years we'd be moving there. But again, we got lucky thanks to the craziness of my wife who thought that she would be able to pull it off somehow. She saw the for sale sign and said that she was going to find a foundation to help us acquire it. It was my turn to tell her, “Yeah, right, you're crazy.” What foundation was going to help us acquire this historic, massive farm? But she proved me wrong. She connected with a foundation, and they helped us with a very generous grant, so we moved over to that bigger farm in 2018. That's where our 290 farm animals reside now.

If you look back at the history of punk rock and hardcore, there's been a long-standing relationship with what I’ll call, “animal consciousness;” particularly, animal rights, vegetarianism and veganism. What do you think about the relationship between this angry, aggressive music and the love and respect for animals?

I think it's been deeply ingrained for a long time. For instance, that Youth of Today “No More” video they shot in the meatpacking district; I just remember the mistreatment of animals being such a focus of the hardcore community at that time. In fact, the first meal I had with anyone who was vegan, other than my sister, and even before Dave Stein, was with Ray Cappo.

We went to lunch with this guy who had a vegan skateboard shoe company. To me, that was such a foreign concept (at the time). He was from Boston, and they were trying to put together some sort of vegan shoe for Ray. I was helping with the legal stuff. Earth Crisis came along a little bit later, but they've been championing animal rights forever. I love that band for everything they have done. They’ve turned a lot of punk rock and hardcore kids into lifelong animal rights people. Steve Reddy from Equal Vision Records is a tremendous Tamerlaine supporter and animal rights advocate.

One of my closest friends, who I talk to just about every day, Sean Muttaqi, was the singer of Vegan Reich, which was one of the early animal rights bands. Then there are the British crust punk bands, so yeah, it was always there.

There are a lot of different topics covered by punk and hardcore bands, and I still love plenty of bands that are meat-eating, heavy drinking bands like Murphy's Law. Jimmy is very much an outspoken champion of animals and is always talking about dog rescue charities on his social media, and doing benefit shows. Jimmy’s not vegan, but I have no doubt in my mind that he loves animals every bit as much as I do. So, social justice and respect for animals in particular - there's such an obvious tie-in with hardcore music.

Tamerlaine being a not-for-profit, how does the place survive day-to-day?

Barely. It's hard. It's a constant struggle. When we had the animals at our much more modest farm, fundraising was relatively easy. There weren't as many moving parts. There weren't as many animals, and there weren't as many staff members, so now, we’re constantly fundraising.

Just to put it in perspective, I'll never be able to give up the day job. I will always be lawyering. In addition to the work that I've done for hardcore bands, thankfully, I have a great practice where I represent a lot of super famous music, as well as other types of clients, handling their trademark and copyright needs.

But all the money that I make gets pumped into the sanctuary. Tamerlaine is my wife’s full-time, seven days a week job, and she works for free. The sanctuary is my second full-time job.

Not only do we work for free but have put all our life savings into it; my salary, everything. People are like, “What's wrong with you? That's crazy!” And the response is, from a financial standpoint, it is crazy. It's the stupidest thing I've ever done. But it is also by far the best thing that I've ever done, and the most rewarding thing that I've ever done. We put in our own money to make up the difference between what we are able to take in from outside donors and grants. We have 15 employees that work at the farm taking care of the animals, and they're not working for free.

Of course, they deserve to be paid for their hard work. Luckily, we have great employees working at the farm. We of course have vet bills, feed costs, we have infrastructure costs... It's a very expensive undertaking. Without our donors, we couldn't possibly do it, because even with putting in our own money to make up the difference at the end of the year, we're still barely scraping by. I say a little prayer whenever I dip my ATM card into the machine, Let's put it that way. But I wouldn't give up what we do for anything.

***

Learn more about Tamerlaine Sanctuary & Preserve at this link, and if you’re so inclined, feel free to donate here.

***